I was recently in Cong, a small village in County Mayo, two and a half hours east of Dublin. Cong is famous for being the place where John Ford filmed The Quiet Man, with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. There’s a replica of the White O’Morn cottage, set up as a museum, and a life size statue of the star couple.

Unfortunately, it absolutely poured with rain the whole time I was there, so I decided not to do the walking tour. I did see the statue from the car, though.

I was in Ireland attending a wedding party for my niece, whose new husband (my nephew-in-law?) is from Cong. I was on my third or fourth Guinness when it struck me. We who in the Seventies were in our twenties are now, in the Twenties, in our seventies. And yet there we are, still partying like it’s 1973. Those of us who are left, that is.

Many did not make it out of that fabled decade, falling to the temptations of the time or the vagaries of fate. Others, over the years, have left by accident or design, by the hand of themselves or others, by ill-health or unfortunate circumstance. As Leonard Cohen asked, who shall I say is calling?

In Dublin I went to Trinity College, to see the Book of Kells and the famous Long Room, which is part of the Old Library. It was orientation day for new students, so to get to there I had to weave my way past the tables enticing new members to the Golf Society (Men) or the Golf Society (Women), stepping over the piled carabiners of the Climbing Club. It’s a long time since I’ve seen the red hammer and sickle flag of the Socialists.

Once inside, I loaded my phone with the app for the audio tour and wandered around. The wall panels were quite good, and the information about Ireland in the 600-800s was interesting.

According to the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, the Book of Kells is “considered a masterpiece of Hiberno-Saxon art [and] is filled with full-page illuminations of breathtaking complexity and intricate interlace patterning that calls to mind the precision of metalwork. Giraldus Cambrensis, who saw the manuscript in Ireland in the twelfth century, describes it as ‘so delicate and subtle, so exact and compact, so full of knots and links, with colors so fresh and vivid that you might say that [it] was the work of an angel.’”

Perhaps. Unfortunately, the person in charge of turning over the pages every eight weeks had left it open at folios 201v-202r: Luke 3. 32-38. For those of you unfamiliar with the Gospel of Luke, and according to the guide, this is the bit where “the ancestors of Jesus Christ are listed in elegant symmetry, … opening with ‘Who was of Naasson’ at the top left-hand folio and closing with ‘Who was of Adam / Who was of God’ at the bottom of the right-hand folio.” Perhaps.

You’ll have to take my word for it, as photographs were not allowed, but basically what I saw was a list. In a long line down both of the open pages. In mediaeval Latin. With the ‘Q’ at the beginning of each line curlicued a little bit. No fresh and vivid colours, no intricate interlace patterning, no knots and links. I’ll have to go again, once they’ve turned it to a different page.

I went up to the Old Library, with its famous Long Room. Here I discovered myself in the middle of a “once in a lifetime” event – they had taken all the books off the shelves for cleaning, and so I had the opportunity to examine the woodwork in unobstructed detail.

I looked at the rows of empty shelves, watched over by the plaster busts of no doubt somewhat confused philosophers, and then exited through the gift shop where I found nothing to buy. Outside, it was raining again, and even the socialists had taken their flag and gone home.

Ireland was one of the few places I have been where there was no reference, however oblique, to Captain James Cook. For that I had to go to London, where I followed Cousin Jimmy’s trail down the Thames, travelling by river boat from the Tower of London to Greenwich. It was a calm morning, early, and Tower Bridge was at its majestic touristy best as the Uberboat passed beneath.

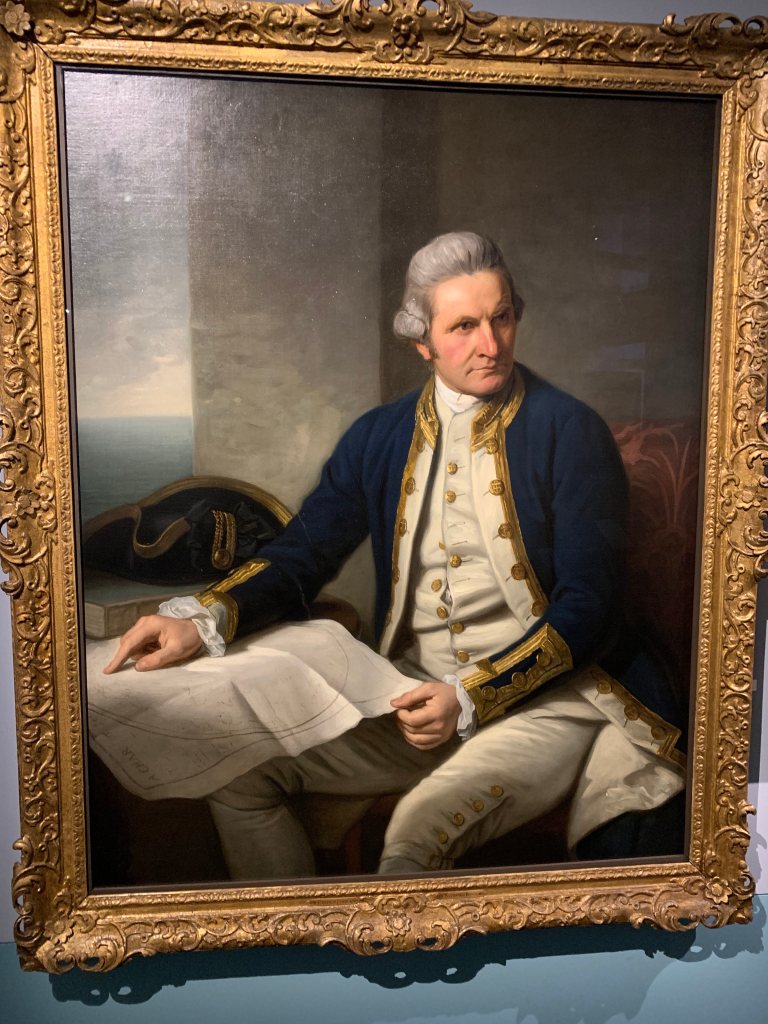

The Maritime Museum has a gallery dedicated to the Pacific, and it was a delight to see the original paintings of illustrations which adorn so many books about Cook’s various explorations. Here, by reputation, is another quiet man.

I spent a happy couple of hours wondering how artists like Hodges managed to produce such exquisite work in what must have been extremely exacting circumstances. It was interesting to observe, though, that the black volcanic gravel beach of Matavai Bay is here shown as an expanse of sun-baked sand. Is that a geological shift over time, I wonder, or simply a case of the artist painting what his mind told him was there rather than what was actually visible?

Perhaps we all only see what our mind tells us should be there? It was my first visit to London since before the pandemic, and at first, I was enthralled by the grandeur and scope of the buildings. From the Wren masterpieces of St. Paul’s Cathedral or St. Martins-in-the-Field, from the solid fastness of the Tower of London to the glittering modernity of the Shard, the architecture is exquisite. But then you look down, at street level, where the pavements are jammed with tourists and locals alike, stepping over litter and around the homeless, milling around in a never-ending dance. The trains were on strike while I was there, and all the doctors in all the hospitals, and the Underground was going to be closed on Wednesday.

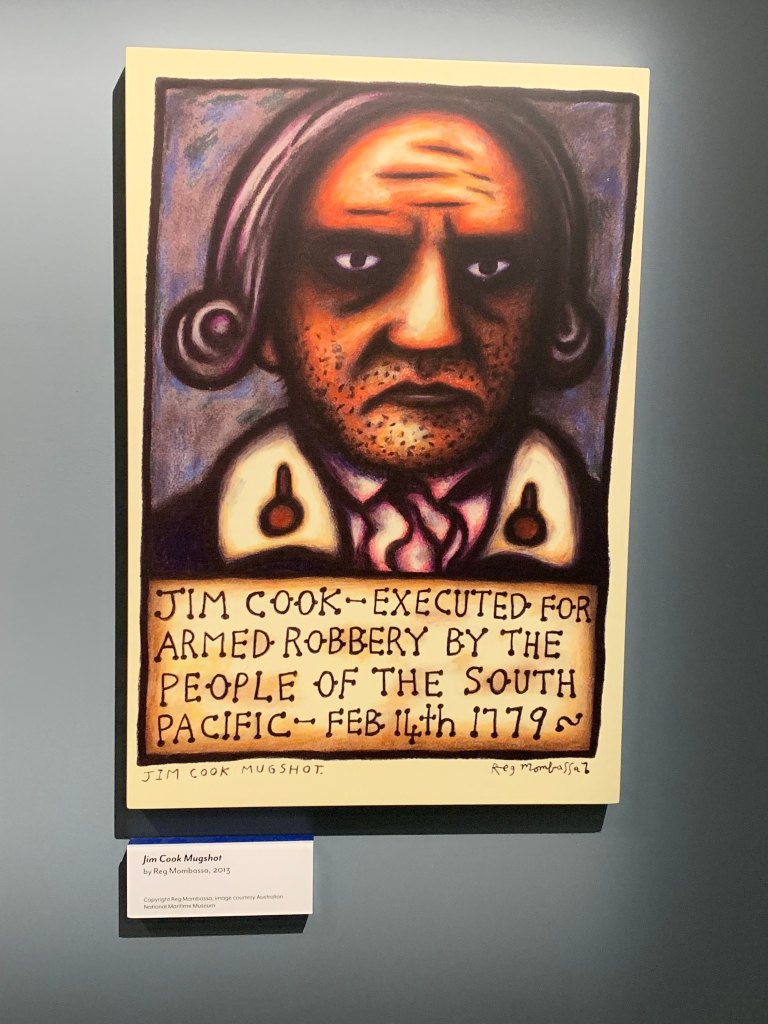

Dirty, busy, crowded, dreary. It sounds just like the London of the eighteenth century. Is it no wonder, then, that Cook and others craved to return to the Pacific? That the men on the Bounty decided that self-exile on Pitcairn was preferable to a return to England? Although, if truth be told, not everyone was happy to see these strangers from a distant land.

Not a sentiment with which I agree, of course, but one thing I have learned over the years is that there is more than one truth in an historical record.